News | 02 March 2023

Demand from municipalities determines whether we establish new schools

There has to be a clear need and desire in a municipality for Internationella Engelska Skolan to consider opening a new school. “The municipality notifies us of its interest, and tells us where the school will be located, when it should open, which years it needs to cover and how big it has to be,” said Jörgen Stenquist, the deputy CEO at IES, who is responsible for the establishment of new schools. “It may be because a new area of the city is being built, or the municipality is competing for a new international company to locate there, or it wants to improve a socially vulnerable area,” he continues.

Jörgen Stenquist, deputy CEO at IES

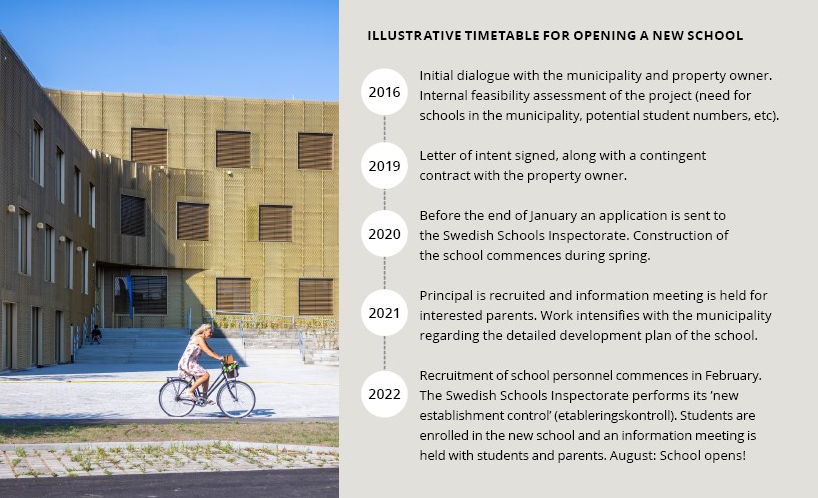

Internationella Engelska Skolan will soon have existed for 30 years and currently runs 45 compulsory schools in Sweden, from Trelleborg in the south to Skellefteå in the north, as well as one upper secondary school on Södermalm in Stockholm. We consequently have tried-and-tested processes for setting up new schools.

“We never make the decision about where we will open a new school on our own accord. It is usually the municipality that sees a need that we could fill, and then they contact us. In some cases contact is made via a construction company which may have been assigned by the municipality to build a new area of the city which includes a school,” says Jörgen Stenquist.

Reduced investment required by the municipality

IES can reduce the investment that municipalities need to put into a new school due to its long-term, close cooperation with big property companies, which is one reason why municipalities are interested.

“To build a new school costs somewhere between SEK 250–800 million, a cost that the municipalities often pass on to a construction company. So they want a solid, longterm tenant – such as IES – to make this an interesting proposition. Our contract usually has a term of 20 years and through our long tenancy, it’s really IES that covers the investment,” says Jörgen Stenquist.

“Furnishing of the school is also required, which is another substantial investment that IES takes on. We invest SEK 25–30 million in furniture and equipment in every new school and continually replace materials that get worn or damaged. IES is often a major and important employer in those municipalities where we open new schools. The municipality also benefits in other ways, for example as we buy services from the local business community”, he continues.

IES does not have any influence over where the school is located, how big it needs to be, which years it has to accommodate or when it has to open – this is all decided by the municipality.

A complement to the existing choice of schools

IES’ international profile is a further reason that so many municipalities welcome the school. Its international profile is a complement to the existing choice of schools.

“We are not interested in driving out other efficient school organisations – we aim to be a complement to them,” comments Jörgen Stenquist.

“Municipalities want us there for different reasons, and that’s why there is also space for IES. Our experience is that local politicians, regardless of political party, are often pragmatic and focus more on the needs of the municipality’s residents than on politics. We have several examples where the desire for the new school stems from the municipality wanting to offer a school with a high standard of quality to improve a socially vulnerable area. There are other examples where the municipality wanted to attract international companies via a school with teaching in English, or perhaps build a new area of the city where we would help attract new residents,” he says.

”As long as there is demand from students and parents, then we’re interested in opening new IES schools.”

International school gave Skellefteå Northvolt

Northvolt’s massive battery factory is an example when different municipalities competed against each other to attract a whole new industry with the potential to increase tax revenues and the number of jobs. Northvolt is investing in one of the biggest industrial projects in Sweden for decades with a factory that is estimated to employ around 4,000 people once it is in full operation in 2023. One of the major criteria in the company’s location decision was access to an international school. The traditionally Social-Democrat-governed municipality wanted be more attractive to Northvolt and enable the company to attract important, international skills. So it approached IES, and we opened our school in the city in 2019.

“This is exactly how it should happen,” comments Jörgen Stenquist.

Collaboration between the municipality and the independent school

Eskilstuna is a good example of how an independent school and a municipality can work together to break a negative trend in an area. When a municipal school in Fröslunda, an area with socio-economic challenges, was moved, the municipality was left with empty premises and high costs. The closure of the school was the start of a downward spiral in the area, and it was followed by the police moving to new premises, the shutting down of the municipality’s social services and the shops leaving the centre. Fröslunda became one of Eskilstuna’s most segregated areas and was put on the police’s list of socially vulnerable areas. When the Social-Democrat-led municipality decided to combine forces to drastically improve the area of Fröslunda a few years ago, IES was a natural partner. We took over the school and a number of other premises that had previously stood empty and made the centre feel unsafe. IES is also part of a new initiative between the municipality and other local stakeholders. The idea is that school staff, social services, the police and after-school staff will collaborate better to detect youngsters who are in the risk zone for criminality.

The Liberal-led Landskrona worked intensively over many years to bring IES to the municipality. It considered that the school, along with attractive new homes, would be important to reversing the negative trend in the municipality and appeal to more businesses and people. The school, which was built for IES, is part of a new area on the outskirts of Landskrona and it opened in 2017.

“As long as there is demand from students and parents, then we’re interested in opening new IES schools. But where and when has to be determined by the municipality’s needs analysis and the student base,” says Jörgen Stenquist.

To read the full quality report, click here.